By Nolan Bishop, The Pioneer

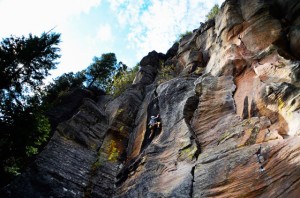

In recent months, members of the Umatilla tribe have initiated conversations with the Forest Service about the usage of Spring Mountain, a site of cultural significance to the tribe and a popular rock climbing destination in northeastern Oregon. Situated just outside of La Grande, Oregon, it is frequently used by the Whitman and Eastern Oregon University climbing communities, as it presents the best outdoor climbing within a two hour drive from either campus. Whitman has been using the mountain regularly since the first routes were bolted, nearly twenty years ago.

In 2002, members of the Umatilla tribe met with National Forest representatives and other members of the climbing community to create a Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) to help ensure respectful use of the cliffs at Spring Mountain. The sessions stalled out, and no agreement was reached. The tribe initiated new meetings with the Forest Service in 2005, and completed a draft, but it was never finalized. Larry Randall, a Umatilla National Forest Ranger with the Walla Walla District spoke to the nature of the current discussion with the tribe.

“It’s time for a fresh look at how things are playing out at the mountain,” said Randall. “The last discussion with the tribe and the climbing community regarding use of the mountain was almost ten years ago now, and the tribe is interested in re-examining the nature of the use the mountain is receiving.”

The mountain is located within the boundaries of Umatilla National Forest, which abuts the Umatilla Indian Reservation. The mountain is considered a sacred site for the Umatilla tribe. In a recent article published by the Confederated Umatilla Journal, Wil Phinney outlined the importance of the cliffs to the tribe.

“Indians who camped eons before at Tillippana, now known as Fox Prairie, considered Spring Mountain a culturally significant site where they paraded on horseback singing songs and performed certain ceremonies,” Phinney wrote.

Because of the importance of the mountain to the Umatilla tribe’s cultural heritage, many individuals within the tribe are concerned about ongoing usage of the mountain by the climbing community. In particular, religious leader Armin Minthorn wants to ensure the respectful use of such a valuable cultural resource.

“The Forest Service is aware [of how the Umatilla feel about Spring Mountain],” said Minthorn. “They understand that Spring Mountain is culturally significant to us. They know that and that’s good. They know they have a responsibility to protect it.”

The tribe’s concerns over the use of the mountain stem primarily from the bolts that have been placed in the cliff face. Chuck Sams, the Communications Director of the Confederated Tribes of the Umatilla Indian Reservation explained some of the potential problems the bolts can create.

“We aren’t only worried about the visual impact of the bolts, but also about the damage they might cause to the cliffs. They can widen fissures and cracks in the rock, and inexperienced climbers with little knowledge of how to set or develop routes can cause damage,” said Sams. “We’re also concerned about the impact that this increased use is having on the area around the cliffs. Even the most attentive stewards of the environment leave their mark on the mountain, causing trail erosion and occasionally trampling vegetation.”

Jeff Bloom, a Recreation Specialist with the Walla Walla Ranger District of Umatilla National Forest, has been involved with the ongoing negotiations.

“The process to determine the cultural importance of a site depends heavily upon what the tribe tells us about their relationship with that site,” said Bloom. “The Forest Service will continue to work with the tribe to find an agreeable solution to the concerns the tribe has raised about Spring Mountain.”

The Forest Service is currently in the process of completing an assessment on the area around Spring Mountain, which includes examining the geology of the mountain and the mechanics of the bolts, as well as the impact that increased use has had on local flora and fauna. Michael Rassbach, District Ranger for the Walla Walla District of the Umatilla National Forest explained that the area has seen a dramatic increase in usage since the last MOU meetings.

“We’re still in the middle of trying to assess where we are now and how it’s changed from the situation at Spring Mountain ten years ago,” said Rassbach. “When we’ve gathered all of the information, we will share that information with the tribe and work with them to develop acceptable limits to activity.”

Whitman Professor Kevin Pogue, who is responsible for the creation of many of the routes on the mountain, was present at the original MOU drafting sessions in 2002, and met periodically with members of the tribe, the Forest Service and other members of the climbing community to voice concerns and attempt to establish an initial agreement. He also helped to mitigate some of the tribe’s initial concerns over use of the area.

“The tribe was worried about the visual impact of the equipment on the wall, and they actually purchased camouflage bolt hangers to replace the ones that were there,” said Pogue. “Myself and other individuals from the local climbing community spent hundreds of hours replacing shiny chains with rap hangers and old steel bolt hangers with custom camouflaged bolt hangers. The tribe actually paid for the new equipment and the climbers installed it.”

In addition to this measure, the draft MOU also included language that excluded the creation of new routes on the mountain. Now, nearly ten years later, the tribe is interested in verifying that the stipulations from the first MOU have been followed. According to Pogue, at the time that he wrote his guide to the mountain, there were 94 sport climbing routes. “Sport climbing” refers to routes which have permanent bolts in place to facilitate climbing. Additionally, there are 45 traditional routes, referring to routes that have no permanent hardware in place, but instead require climbers to install their own protective devices while climbing.

Following recent concern that there has been new route development, and that some of the camouflaged bolts have been replaced or the paint has worn off, the Umatilla tribe approached the Forest Service requesting an inventory of the routes at Spring Mountain. The Forest Service approached Whitman’s Outdoor Program for assistance in completing this inventory. As Assistant Director of the Whitman College Outdoor Program, Stuart Chapin has been assisting the Forest Service in finding students to complete the inventory.

“Whitman was asked to help the Forest Service because of the Outdoor Program’s extensive involvement in Umatilla National Forest,” said Chapin. “We run dozens of trips up there every year, and so the Forest Service knows who we are and what we do.”

Whitman students Carl Garrett (‘15) and Woodrow Jacobson (‘15) will work with the Forest Service to count the number of routes present on the mountain.

“I’m excited to be involved in this project because it combines elements from my academic focus as an ES/Politics major; my career interests in natural resource management; and my pursuits in climbing and the outdoors,” wrote Garrett in an email.

If Garrett and Jacobson discover that more routes have been put up since the initial concerns were raised in 2002, new routes may b be removed. Chapin is unsure as to whether Garrett and Jacobson will find new routes, though he believes it is possible.

“The likelihood, I would say attributable to a few things, is that we’ll find a couple of new routes. The first reason is that there’s not a whole lot of information at the mountain about what’s okay in terms of putting up new routes,” said Chapin. “One of the other reasons that there may be new routes is that there may have been a few members of the climbing community that weren’t on board with the MOU, or just didn’t know about it, so they may not have been following the stipulations of the agreement. The climbing community is a broad and diffuse group so it’s hard to communicate within that group and it’s hard to be consistent in terms of the treatment of any one site.”

Pogue, on the other hand, is confident that no new routes will be present.

“As far as I know, there have been no new routes established,” said Pogue. “I was a principal route developer at Spring, and I haven’t put up any new routes since the conversation with the tribe started. Route development has stopped up there. The tribe shouldn’t have anything to worry about in terms of continuing development.”

Chapin underscored the importance of the consulting role Whitman is playing for the Forest Service, and suggested that openness and good will on the climbing community’s end will be an asset in maintaining access to the mountain.

“I think that it will probably end up being a positive thing with the tribe because we probably won’t find very many new routes, and when the tribe went up to the mountain and looked around, they saw a lot of bolts and thought that there’d been new routes put up. It will be reassuring for them to know that the spirit of the agreement hasn’t actually been violated. They may be expecting a 25 to 50 percent increase in the number of bolts and we may report a 3 percent increase. I think it will be a surprisingly small number.

Whitman is also taking a risk by helping the Forest Service with this project. Chapin explained some of the potential backlash that could stem from Whitman’s compliance with the Forest Service and tribe.

“Our involvement certainly runs the risk of being somewhat controversial within the climbing community because if we go up there and identify routes that weren’t there when the initial concerns were raised, it could lead to the tribe having a negative reaction because the principles in the MOU weren’t necessarily adhered to strictly,” said Chapin. “If routes end up being removed, whoever put that route up could be upset about that, and we could be in for some of the blame for that because we helped take the inventory and remove routes that violated the MOU draft. And that’s definitely a risk we take by cooperating with the Forest Service in this process.”

In the end however, the conversations between the Umatilla tribe, the Forest Service and the climbing community have always been characterized by good will and understanding from each party.

“During the meetings to draft the first MOU, we expressed what an important resource it is for us, how it’s the best climbing within two hours drive from Walla Walla, how we respect it as a beautiful place,” said Pogue. “Climbers love nature, we don’t just view it as an outdoor climbing gym. People love to be out there in nature, and camp out. It’s a great resource, and we certainly respect the place.”

Chapin echoed the same sentiment, and expressed his enthusiasm about having an opportunity to speak directly with the tribe about the mountain in the future.

“It’s not a right to climb at Spring Mountain, it’s a privilege, and if there’s an agreement in place that allows us to climb up there, then we need to uphold that to the best of our ability,” said Chapin. “I hope to get the opportunity to meet with representatives of the tribe at some point, and to demonstrate that we are totally willing to listen and to do whatever we can to accommodate their interests. I look forward to hearing more about the history and the importance of Spring Mountain for the Umatilla. It’s important to me to help respect the wishes of the tribe. They’ve been here for a long long time, and have an important view of the way the world should work.”