LUCAS SCHAUMBERG

News Writer

schaumlc@plu.edu

“I’ve been knocked down before,” says Felix Guzman. “But this time feels as though I’ve been hit when I was still getting back up. If something happens, then I don’t know if I can get back up again. I might be down for good this time.”

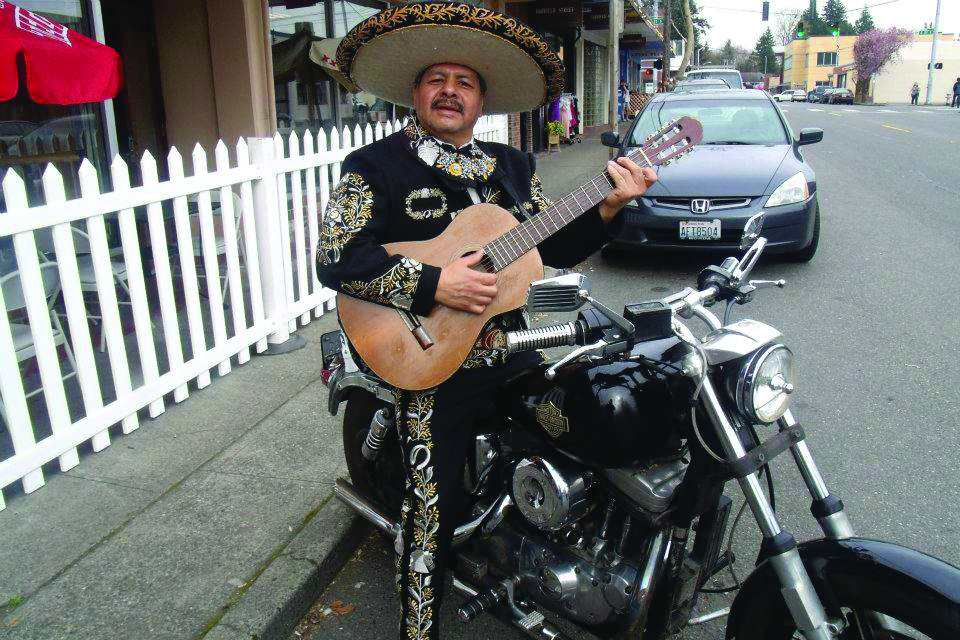

Guzman, who owns Reyna’s – a Mexican restaurant just blocks from PLU – says he has dealt with more worries in the past couple months than any other time he can recall. He’s lived here for more than 20 years and started Reyna’s from nothing, hand-painting the building and crafting the menu. He doesn’t know if his livelihood, the restaurant, which feeds his children and constitutes a huge part of his identity, will make it to see next spring. All he can do currently is work tireless hours, hoping the tides of his misfortune will cease to rise.

Guzman is usually an animated man, constantly weaving throughout his restaurant to chat with his customers. Tonight, the emptiness of the restaurant makes him seem especially weary. His hands, still scented with tomatoes and diced onions, have fresh pink burn scars on them. He can’t afford any new hires, he explains, and must fry the rice dishes himself.

Guzman traces the beginnings of his financial shakiness back to the 2008 recession, when the United States experienced high unemployment rates. Parkland was hit disproportionately hard – the unemployment rate is about ten percent above the national average, even eight years later. He and his wife have sunk almost 20,000 dollars into renovation and menu revamps, but his efforts to rejuvenate business remain fruitless. Changes with student parking and a lack of advertising and name recognition have cut into his customer base have cut into the restaurant. It physically shows. One of the first things you notice walking into the restaurant is an unlit and institutional room sectioned off by a purple curtain. Reyna’s sold the space just to barely keep afloat.

When asked about the future of his restaurant, Guzman says he genuinely doesn’t know how things will play out. He’s trying to find if there’s anything he can do to put the fate of the restaurant back into his own hands. Felix is far too busy during the day to sit and think about the questions that loop through his mind. But now, with the place shuttering closed for the night, his worries unspool. He shares them, in a soft voice colored with a lilting north Mexican accent, over the sounds of Univision and dishwashers chattering in the background. No murmurs of conversation from customers can be overheard.

“I’ve been knocked down before, but this time feels as though I’ve been hit when I was still getting back up. If something happens, then I don’t know if I can get back up again. I might be down for good this time.”

Felix Guzman; Owner of “Reyna’s”

When Guzman was a teenager working at a tourist shop in Tijuana, it was his skill for conversing with customers that got him ahead. He still catches himself reminiscing about Mexico – about the family that has there, the welcoming bars and vast expanse and desert warmth of the Sonoran night sky. This restaurant connects him and his kids to his heritage there.

Here in Parkland, however, is where he’s planted his roots. His whole family is built around the cornerstone of his restaurant. His wife, the restaraunt’s namesake, is much more reserved then her husband, though Reyna gives off more of a dignified calm than reticence. She sits in the corner, letting her legs rest from a 12-hour day and watches their 6-year-old son play. Felix says customers sometimes complain about his kid prancing throughout the restaurant, but trying to raise him while working fulltime means keeping him around. He has an 11-year-old daughter who helps out occasionally, though she’s more interested in her studies, notes Mrs. Guzman with pride. It’s the uncertainty about their future that Mr. and Mrs. Guzman feel most acutely.

Guzman says the grime and grit of the neighborhood (a shop next door was recently busted as a drug front, according to local police) is a contributing factor to his financial slump. Felix says that the business side of PLU was good about helping him for the last four years, but things changed last March. There’s been multiple problems with the PLU contractor, who oversees the business on Garfield Street, and Guzman has difficulty contacting the administration for the assistance he needs to stay. He’s had his advertising torn down from the walls of PLU and has had trouble buying ads in the local paper. He doesn’t know how effective print advertisement would be in a digitized age, either.

Internet apps like Yelp may help consumers, but these digital reviewing apps are just another wellspring of anxiety for restaurant owners like Guzman. More than once he brings up a story of a customer being unsatisfied with the wait staff and burning him on the social media. He holds a respectable 3 1/2 star rating on the website, but this incident in particular still seems to haunt him. He brings it up twice during our interview.

Yet Guzman doesn’t seem angry or disappointed at any of this. He doesn’t harbor ill will towards anyone. He just wants to know if there’s anything he can do, what would be effective. “My motto is this: your customers are family. You invite them in for a family meal, and they will come back.” Guzman believes that his new adjustments to his menu, including a happy hour with a steep student discount, will be the catalyst that the slogging business waits for.

“Students are my main livelihood. The best part of my day is going up to tables, talking to my customers, talking to students,” says Mr. Guzman, stroking his mustache pensively.

His website is full of pictures of past and present Lutes, but there are fewer and fewer students these days, which he believes are related to meal plans and changes in student parking. He’s tried advertising in the student paper, or on KPLU, but he received no response. He needed KPLU to cut a deal with him so he could afford the rates, but things fell apart in the last minute. The posters he puts up around campus are soon torn down, perhaps because of difficulty reaching the right channels. It’s impossible to forecast if his livelihood will be torn down as well.

When pressure piles up in Guzman’s life, he tells me, he feels stress manifest in an unusual place. “By the end of the day,” Guzman said, “I can barely read. I’m on my feet all day and have a bad back, but I feel it in my eyes.”

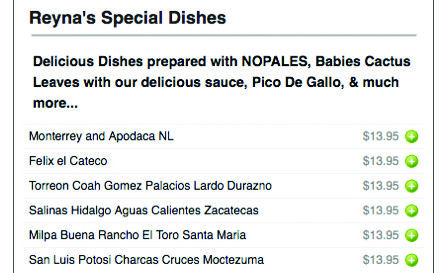

REYNA’S SPECIALTY

Reyna’s owner Felix Guzman says the pride of his menu is Nopales, a traditional folk-cure dish which uses baby cactus leaves as a primary ingredient. He prepares them in a homemade sauce with a smokiness indicative of Tejano (Texan/Hispanic) culture. He thinks the most popular dish at the restaraunt is Carne Asada, which he prepares himself almost every day. Almost all of the recipes are from family or friends – and he’s already passed them down to his kids. His 11-year-old daughter is apparently the best rice cook in the family.