Rizelle Rosales; Mast Magazine Co-Editor; rosalera@plu.edu

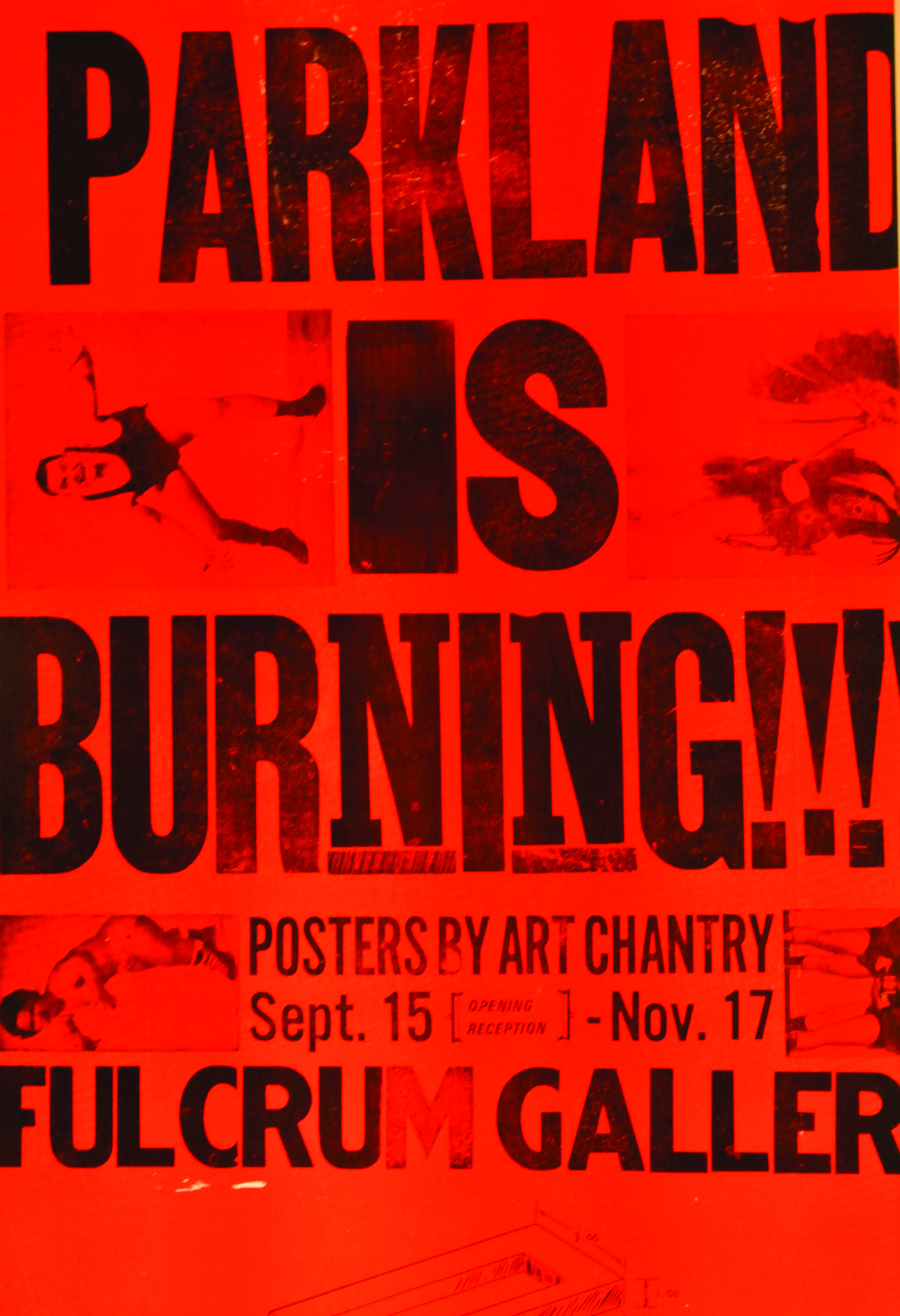

In 2011, Tacoma’s grunge fans, graphic designers, DIY devotees and subculture fanatics gathered to celebrate the Fulcrum Gallery’s exhibition of Art Chantry’s legendary posters, titled “Parkland is Burning!!!” Based in both Seattle and Tacoma, Chantry is a household name in the Pacific Northwest grunge scene. His work is unapologetically provocative, confrontational, even hostile. The posters, in a sense, reflect elements of Parkland itself, a collage of old vignettes and neon signs. Burning, but never burnt out.

The history of the art community in Tacoma is vast, from the humble beginnings of the Tacoma Art League in 1892 to today’s involvement-oriented collectives like the Fab-5 and Spaceworks. The height of Tacoma’s artistic accomplishments and history casts a long shadow. This is where we find Parkland, with its artistic expressions lying humbly in the backdrop.

One of the earliest artists on record is F. Mason Holmes, who lived in Parkland for the first half of the 20th century. He painted landscapes in different media and taught art at Pacific Lutheran University. His paintings are still in circulation today, with his legacy lying in his canvas drawings of Pacific Northwest landscapes.

Ed Kane’s name might not immediately ring a bell, but it only takes a stroll down the street to see his influence in Parkland: the murals on Garfield Street are all his doing. His works have graced the bar at Reyna’s Mexican Restaurant as well as the Northern Pacific Coffee Company bathroom. Because of closings and renovations along Garfield Street, several of his murals have been lost. There’s still one that stands next to the purple Garfield Street House, portraying a realistic reflection of the street as if the surface were a mirror.

The posters, in a sense, reflect elements of Parkland itself, a collage of old vignettes and neon signs. Burning, but never burnt out.

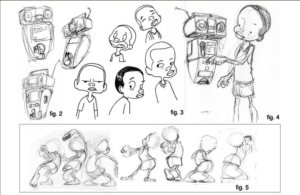

One of Parkland’s prominent artists from the past decade is from our own living room. Nick Butler, a former PLU faculty member, is a jack of all trades. He is the founder of Turtledust Media, a digital production studio started in 2003. Originally based out of his garage in Parkland, Butler and his students worked on a variety of projects, including a horror film titled “Imago,” storyboards for Hollywood and independent productions, as well as comics and animated short films. More recent projects include his original animated films “Kat and Bunnie” and “Peanut Butter Jelly Jam.” You may have seen Butler’s work at Emerald City Comic Con 2017.

Local artist Robert Hull owned two small shops in Parkland that sold curiosity items — the weird, wild and wonderful sort. Mystical mermaid keepsakes, walrus tusks, ebony carvings from overseas, you name it. He’s traveled all around the world and specializes in art of all kinds: woven macrame textiles, beadwork, paintings, carvings. The two businesses have since closed down, but he has continued to bring art to the community through the Stitchery Club at Trinity Lutheran Church. Bringing beads and jewelry to share from his travels, he has attracted quite an attendance for the humble Stitchery Club. Hull plans on opening up the group to other forms of art outside of stitchery. Hull says, “I like being part of the group. Now I’m going to bring in other things, teach how to decoupage and make macrame and other things. I want to bring in different things all the time — all kinds of art.”

A large element of Parkland art is PLU itself. The conversation about Parkland’s art community cannot exist without the school rooted in it. Its facilities help foster student artists, support local artists and feature faculty. The University Gallery features curated shows of local artistry, selections from PLU’s permanent collection, student juried shows and a senior exhibition. The Scandinavian Center is also a large venue for art, considering its strong presence in the nationwide Norwegian community. Their past exhibitions have featured works that reflect dynamic Norwegian narratives, actively remembering PLU’s heritage.

The Parkland Post Office was built because business owners and members of the community joined forces to petition for better mail service in 1954. Fifty years later, a new generation gathered together to create the community mural that adorns the post office today. With clean lines, fine details and bright colors, the mural has become a quintessential signature in the Parkland landscape.

Saiyare Refaei, ‘14, co-organizer and lead artist, was inspired to design the mural after returning from studying away in Oaxaca, Mexico, where see saw breathtaking murals in community spaces. Along with co-organizer Carly Brook, ‘15, they gathered the creative opinions, stories and narratives of the community by organizing forums and opportunities for Parkland residents to voice their values and visual goals for the mural.

Like its art, Parkland is complex, asymmetrical, dynamic and resilient in its ability to thrive in obscurity.

Community art requires a vast amount of careful planning because accurate representation is essential to creating a piece both of and for the people. Without careful consideration, the mural could have resulted in a mediocre project with a two-dimensional narrative, painted with good intentions like a toothy fake smile, complete with a PLU stamp.

Knowing this, the organizing team for the mural took no shortcuts, taking a holistic perspective in designing the piece by including the Parkland community at every step of the process. Made possible by donations and a grant from the Pierce County Arts Commission, the mural was painted by Refaei and volunteers from all around Parkland. The final product is a portrayal of the complex narrative of Parkland, a multidimensional collection of the values, truths and aspirations of this community.

Interestingly enough, there’s a term in medicine called the “Parkland formula,” which is used to treat burn patients, to treat those who truly know what heat is capable of. Here, the heat of the socioeconomic flame is no stranger. Parkland may even get charred around the edges — but this community has a method, a formula that keeps it going — living.

There’s an art behind Parkland. It lies in the soil of the community gardens, in strange mossy lawn ornaments, in the way every house breathes life differently, in the passionate librarians teaching English classes, in the AMPM employee who plays show tunes during the graveyard shift. Like its art, Parkland is complex, asymmetrical, dynamic and resilient in its ability to thrive in obscurity. Perhaps this is what Chantry meant by his exhibition title. Parkland isn’t burnt — it’s burning, hot and bright in the present tense.