By Gurjot Kang

Reporter

As I patiently waited in line, behind a queue of eager tourists, to enter the British Museum, I couldn’t help but wonder what new and exciting information lingered nearby in one of the museum’s fascinating global exhibits. There’s so much life and story that lies behind ancient artifacts and cultural mementos from the past. It’s easy to forgo the thought of precious time as you make your way up the museum’s giant steps and find yourself lost in between long white marble corridors.

Ever since I was a kid, the history of my people in context to the surrounding world has always intrigued me. My brother and I would spend late evenings having hour-long discussions over topics, such as the involvement of Sikh Punjabi soldiers in the World Wars, the negative effects of the partition of India on the Punjabi community, or the lives lost during the 1984 Sikh massacre. These conversations with my brother would provide a sort of emotional release. For me, these chats were the closest it ever came to learning a part of our family’s cultural history. They’d highlight stories never told on a national pedestal and the ongoing social justice endeavors of the Sikh Punjabi community.

I wasn’t pleased with the brief, one-day glossed over history lessons on India taught throughout my K-12 education. The most they ever covered were: “there was once a man named Gandhi who led a peaceful revolution against the British Empire that freed India—the end.” That was all it took to gain independence. This condensing of facts and timelines left out important narratives and prevented folks from learning about a history unfamiliar to theirs. My classes didn’t feature any further discussion on post-independence India.

There were no plans to talk about the aftereffects of colonialism. And there was definitely no mention of the bloody partition that took place after the British hurriedly split the subcontinent into India and Pakistan, causing one of the largest migrations in history. A migration that forced 15 million out of their homes and led to the death of over a million people.

One of the most violent regions where sectarian conflict broke out was in the state of Punjab, where my family’s from. My grandparents were alive during the time of partition, yet I’ve never been able to ask them about their accounts of this history. Now that I’m old enough to understand the significance of recording their memories of such crucial events, it’s unfortunately too late.

So, when I entered the museum’s exhibition on cultural artifacts from India, I was surprised nonetheless to find a small section dedicated toward Sikhism. It was in this corner that I spent nearly an hour taking photos and carefully soaking up and reading all the little captions accompanying each relic.

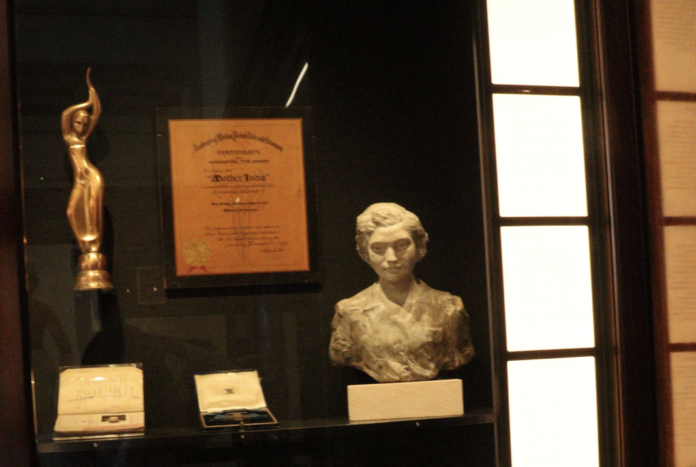

The artifacts on display included: a golden sari from the Punjabi British Suffragette and leader for women’s rights Sophia Duleep Singh (1876-1948), a small figurine of Bhagat Singh (young socialist activist for India’s independence movement), coins from the original Sikh Kingdom in Punjab, a beautifully engraved shield representing Maharaja Ranjit Singh (founder of the Sikh Empire), and a replica of a Sikh fortress turban worn by warriors in the armed Sikh order of Akali Nihangs.

This display opened up a world of Sikh history, with icons like Sophia Duleep Singh, that I have yet to discover. The experience of learning about the Sikh empire from Sunday school at the Sikh gurduwara versus seeing the coins from the kingdom in person was quite startling. For the first time, I was able to see objects and visuals from a history my ancestors were a part of—and that I was proud of. There is something so refreshing about the positive representation of one’s cultural history that everyone deserves to experience, especially first-generation Americans from immigrant families.

From the moment I left the museum, I knew that when my parents visited London in December, this little corner of the British Museum would be one of the first places I’d take them to visit. A home away from home.